UNDER THREADPhoto Series

20199 Artworks

Thread and photography operate simultaneously as tools and as weapons. Both bind, connect, and preserve; both can also restrain, obscure, and harm. Thread acts directly on the body, while photography fixes the trace of that action in time. One inscribes pressure; the other ensures its visibility.

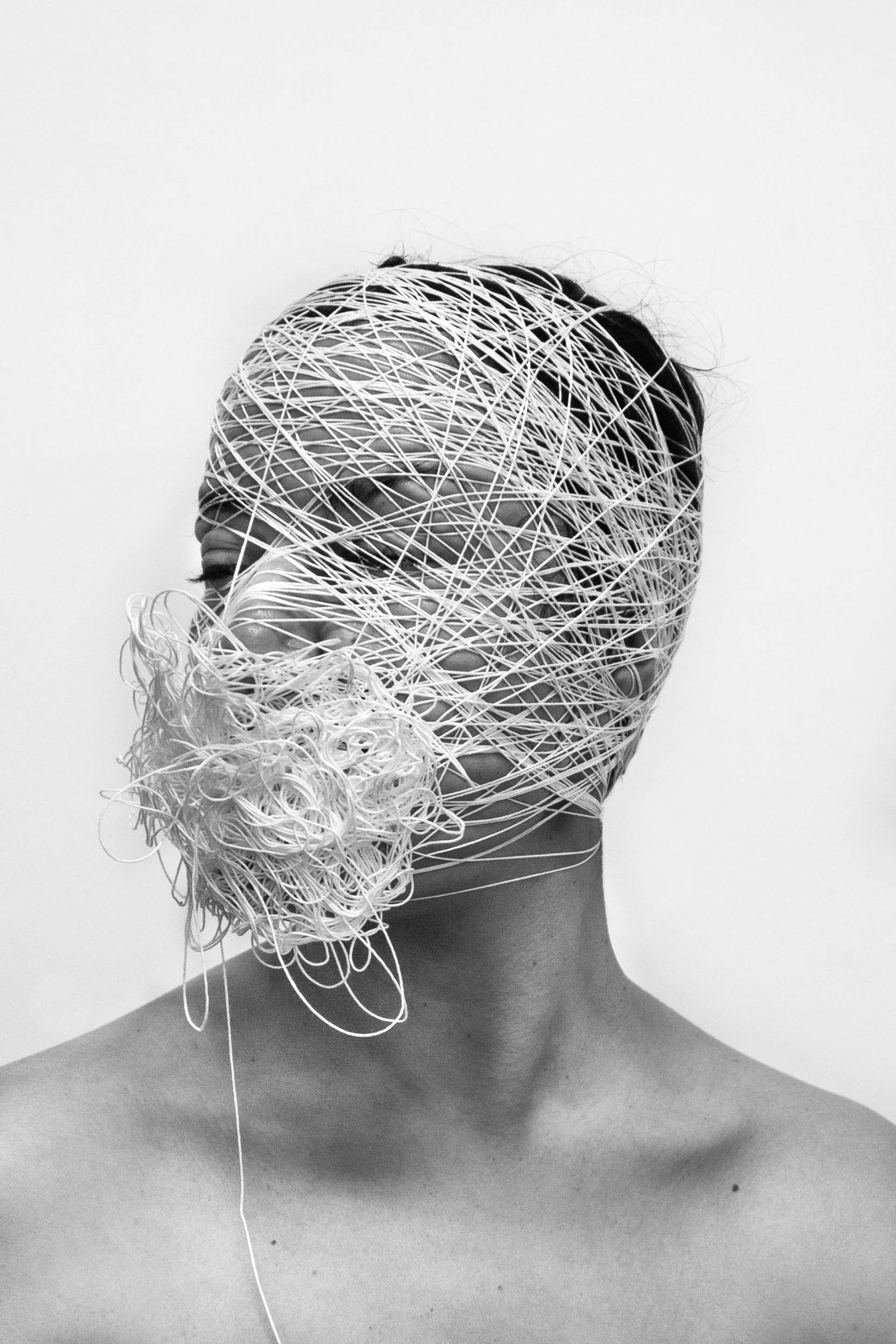

UNDER THREAD (2019) consists of a single image presented as part of a sequence and marks a rupture in my practice. It is the first and only time—up to this point—that I reveal a face, and that face is my own. The work originated as a performance unfolding over time, in which I wrapped myself, and was wrapped, in thread. The thread was woven, spun, layered, and later unspun. This gradual accumulation and release produced a progression of sensations: anticipation, anxiety, fear, suffocation, vulnerability—followed by a relief that was never complete.

As the thread moved across the body, it formed a web—both physical and psychological. The process echoed the logic of the spider: simultaneously the maker of the web and the one held within it. Weaving and unweaving mirrored the experience of becoming entangled in dense networks of information—news cycles, media narratives, social platforms, overlapping voices in multiple languages—each offering competing interpretations of the same events. Immersion promises clarity, yet excess produces paralysis.

The work asks what it means to truly engage these webs of perception. At what point does seeking understanding become entanglement? When meaning multiplies endlessly, deciphering facts gives way to confronting something more elemental: our shared humanity and our limited capacity to grasp suffering from a distance.

As the thread was unspun, it left marks on the body—indentations and impressions across the face, like traces that linger after sleep. These marks resemble how war is often encountered: impact without direct contact, trauma translated into surface and trace. And yet, they are not war. I retain the ability to step away.

This dissonance—between proximity and distance, witnessing and escape—sits at the core of the work. Here, thread ceases to function as protection and becomes restraint. Despite effort, care, and intention—despite the desire to mend or help—the body remains bound. Exposure increases. Repair becomes unraveling.

The performance itself no longer exists. What endures is photography. The images are titled sequentially, one through eight. While each photograph can stand alone, together they form a temporal arc: containment, tension, release, and residue. Photography does not merely document the performance; it completes it. The thread marks the body, and the camera holds those marks in place. What could disappear becomes evidence.

The viewer bears witness. To look is to enter the afterlife of the performance, positioned between intimacy and safety. Like images of war, the photographs ask us to confront trace without inhabiting cause.

March 19, 2023 marked the seventh anniversary of the war in Yemen. One of the world’s youngest nations, the United States, has been central to what is widely recognized as today’s worst humanitarian crisis, participating in the erasure of one of the world’s oldest civilizations. Yet the war is frequently framed as distant or complex, rather than acknowledged as a crisis sustained by U.S. policy and government-backed corporations.

I engage UNDER THREAD as a citizen of Yemen and of the United States. The work asks who is responsible for the wars we participate in as a nation—governments, citizens, or the corporations that fund power and profit from violence. While the U.S. is often understood as a democracy, it functions as a republic in which elected officials—and those who place them in office—make decisions on behalf of the people.

The web created by this structure presents itself as protection while operating as restraint. Within it, crises like Yemen become obscured by saturation—by data, conflicting narratives, and strategic distraction—while weapons and capital move freely through a proxy war fueled by Saudi Arabia and Iran.

UNDER THREAD tears at this web. It names restraint where protection is promised. It insists on the body, the face, and the trace, refusing abstraction in favor of presence.

This marks the point at which my practice expands. Working extensively with textile, it is significant that unraveling occurs through thread itself. From this rupture, the work moves outward—into installation, mural, sculpture, performance, and speculative futurism. Eyes emerge. The gaze returns. What follows is not a departure from textile, but an expansion from it—when material becomes structure, structure becomes system, and system demands to be seen.